The Nature

Observer’s Journal

The Nature

Observer’s Journal

Phasey Bean Blues

Chuck Tague

If I hadn’t seen the yellow wings I wouldn’t have stopped. A half dozen Cloudless Sulphurs flitted and floated around a clump of Phasey Beans between the road and the ditch. The knee-high plants had long-stalked flowers that resembled maroon boxing gloves. These are a potential host plant for the sulphurs so I pulled over to possibly get a photograph of an ovipositing female or a caterpillar.

Phasey Bean blossom

The sulphurs were all nectar sipping males but fifteen or more Ceruanus Blues flushed in a whirl of tiny wings and blue flashes as I approached. None flew higher than my shin and most disappeared into the Phasey Beans.

I descended into the ditch so I could examine the plants and the blues without belly-crawling through the sand. Ceraunus Blue is by far the most common little blue butterfly in Florida. It’s in the Gossamer Wing family, a large and diverse group of small to medium-sized butterflies. The Blues, sub-family, Polyommatinae, are small to very small. The Eastern Pygmy Blue is eastern North America’s smallest butterfly with a half-inch wingspan. The Ceraunus Blues is not much larger. Spread out its wings would barely cover a nickel.

Some of the blues drank nectar from the flowers. Some patrolled the tops of the Phasey Beans. Others engaged in mock combat, chasing each other and flashing blue wings. These were males; the upper surface of the females’ wings are dark brown with only a touch of iridescence at the base.

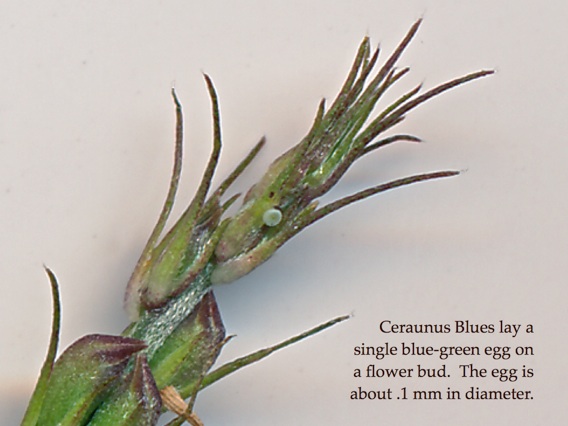

A mated pair copulated in a nearby Partridge Pea. A female hovered over a cluster of Phasey Bean buds and gently touched them with her abdomen. After she moved I found an egg hidden between two bud scales. It was flat and light blue, about a tenth of a millimeter in diameter.

I searched through the plants for caterpillars although I knew it would a challenge. Unlike Monarch larvae, blues have no chemical defenses to repel predators or parasites. Nor do they have false eyespots or frightening spines. They rely on their ability to either hide, or blend in with their host plant. The peculiar creature’s legs are short and hidden by its flattened body. It looks more like a sowbug or trilobite than a caterpillar.

Ceraunus Blue caterpillar

They are not totally defenseless, however. Like many other gossamer-wing species, Ceraunus Blues engage in a mutualistic association -- they recruit ants as body guards. This relationship benefits both species. If a wasp or spider approaches, the ants attack. The caterpillar rewards its protectors with honeydew, a nutritious fluid it secretes from glands on its back.

Two glands on the Ceraunus Blue larva’s back secrete honeydew

Unlike aphids, which have a similar relationship with ants, blue caterpillars do not automatically give up their honeydew; they must first be stimulated. The ants stroke the caterpillar with their antennae. I’d read some species of blue caterpillars call their protectors by mimicking ant sounds. I didn’t know ants communicated with sound.

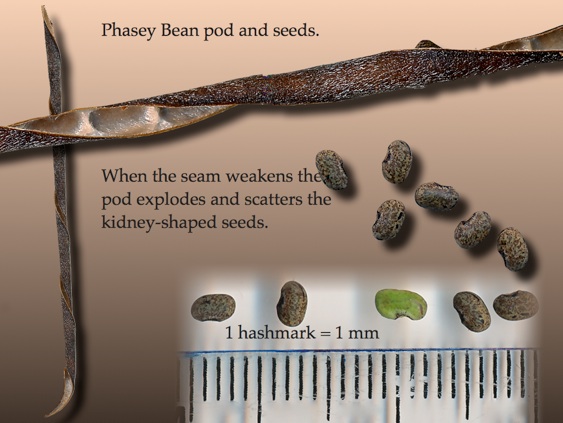

I figured if I found the ants they might lead me to a caterpillar. I didn’t have search long for the ants. I touched a plant and three or four large, red and black ants rushed toward my fingers. After I examined the buds, flowers and the flower stalks with no luck I checked the seed pods. Many projected at a downward angle from the plant stems. The lower pods were brown and dried with a spiraling seam. When I picked one it exploded much like the jewelweed pods I used to pinch in Pennsylvania. Seeds shot in all directions. One dropped into my hand. It was spotted gray and kidney-shaped, the size of a pencil point.

Then I noticed small holes in the green upper pods. These pods were thin cylinders about three inches long -- true string beans. I suspected caterpillars in their early stages were inside but I didn’t want to disturb them. On other pods I found chewed circles. Caterpillars were at work.

I touched a green pod and two ants rushed down from the flowers. Another charged up the stem. These ants meant business -- and there it was. A lime-green bristly bulge on the bean with a yellow pinstripe, like an old Volkswagen about 8 millimeters long. I backed off a few feet, enough to set up my camera. This satisfied the ants and they resumed their duties. One moved to the caterpillar’s front, another to the rear. The third took a position on the flower stalk below the bean pod. If a predator crawled up it would have to go through the sentry ant to get at the caterpillar.

The ant at the front massaged the caterpillar’s head while the rear one drank its honeydew. As I watched they changed positions several times. The insects were perfectly at ease and unaware of me as I watched and photographed them. I, on the other hand, grew more and more uncomfortable. As I knelt in the dry ditch a pickup truck went by and a cloud of dust settled on me. I was folded like an accordion as flat as I could to look through the viewfinder. The coarse sand dug into my knees and my old joints resisted. The sun was directly overhead and sweat dripped into my eyes. I wiggled to get lower and I discovered there was yet another partner in the bean-butterfly-ant association. Mixed in with the bean plants were clumps of Sandspurs.

Coastal Sandspur, Cenchrus spinifex

Sandspur is a grass with a remarkable strategy to discourage herbivores like deer and rabbits. It’s seeds resemble kernels of dried corn with long sharp projections. The spine-like projections are tipped with downward pointing barbs. Any animal that bites into a Sandspur clump gets a mouth full of pain. Any animal that walks through sandspurs comes out with its feet and legs coated with painful hitchhikers. These cling-ons don’t come out easily so the seeds are dispersed great distances. Plants like Phasey Bean that grow in proximity to sand spurs also benefit. So do the ants and caterpillars that live on these plants. Me, not so much.

No grazer will bite into this Phasey Bean leaf.

Fifteen minutes was all I could endure. I’ve read about the ant-caterpillar association but I was thrilled to get a glimpse into the complex insect world.

Note: I collected the caterpillar and put it in terrarium safe from predators and parasites. Two days later it formed a chrysalis (7 mm long). I will release the adult in Tiger Bay State Forest, near the PhaseyBeans patch.

Phasey Bean, Macroptilium lathyroides, is native to tropical America. It was introduced as pasture forage and is now well established along roadsides and disturbed sites in Florida.

Sunday, August 26, 2012